Coming Soon to Arno…

November 16

Steve @RESA all day M-STEP data workshop

Book Fair preview begins

November 17

Steve@RESA 7:30-10:00

November 18

Kinder math release time 8:30-9:30

Kids Hope Pizza party- Send your kids to the cafe at 2:00

November 19

Math Data release time per schedule

Principal for a day- Tony K

P/T conferences begin 5:00- PLEASE let me know if you need me to attend a conference

Pizza Dinner will be in the lounge by 4:00

November 20

Principal for a day- Vinnie K

November 23

Student 1/2 day- 11:40 dismissal

P/T conf. 12:45/5:00

November 24

Nothing Scheduled

November 25-27

No school- Happy Thanksgiving!

Data Day- Tell your story

We have secured floaters (subs) in the buildings so that the full grade level may attend that day. An invitation was placed in your mailboxes. On the invitation we highlighted “What To Bring” but you certainly can supplement with extra materials.

This is your story, an opportunity for our teachers to share data across the grade level. This will not be an administrator led meeting, we are excited to listen in and contribute to a collaborative discussion.

Please read the article: Why teachers must be data experts

What To Bring:

- 1st Quarter Math Assessments

- Student DATA Sheets (from 1st quarter assessment)

- NWEA Data

- DRA Data

- Other…

The schedule is as follows: Arno Elementary

8:45-9:30 Grade 3

9:-35-10:15 Grade 5

10:20-11:05 Grade 2

11:10-11:55 Grade 4

12:45-1:30 Grade 1

1:45-2:30 Grade K

Why Teachers Must Be Data Experts

Jennifer Morrison

An award-winning teacher proposes three attitude shifts that would help teachers learn to love data.

I’m coming clean right here, right now. I’m a practicing classroom teacher, and I love data. Data connect me to my students and their learning, push me to high levels of reflection on my practice, and spur me to engage in dialogue with colleagues, students, and parents.

Unfortunately, most teachers do not share my view of data as a resource that helps them teach better; many experience it as unfamiliar or threatening. In the wake of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), schools are swimming (sometimes drowning) in standardized test data. Districts and administrators are trying to help teachers stay afloat by setting up lanes and lessons in the pool and by coaching (or sometimes haranguing) teachers to the finish line of yearly data-crunching exercises. But we must ask ourselves how sustainable this approach to data is—and whether it’s good for teachers or students.

Although coaching teachers in using data helps them feel less overwhelmed by it, if teachers are ever to use data powerfully, they must become the coaches, helping themselves and colleagues draw on data to guide student learning, find answers to important questions, and analyze and reflect together on teaching practice.

Teachers will take the initiative on this kind of self-coaching if administrators and teacher leaders facilitate three essential changes in how teachers approach data. Teachers must begin to

- Realize that data include more than end-of-year standardized test scores.

- View collecting data as a way to investigate the many questions about students, teaching practices, and learning that arise for any committed teacher.

- Talk with one another about what data reveal and how to build on those revelations.

I had to come to these realizations myself before I achieved my happy partnership with data, which did not happen until well after I had established myself as a teacher. In the past few years, I’ve consulted with school districts and found strategies that help other teachers develop more comfortable relationships with data.

Data, More Than Test Scores

When it comes to teaching, I disagree with British physicist Lord Kelvin, who said, “When you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind.” In teaching, relationships and perceptions matter as much as curriculum and practice. Numbers are important, but they can’t provide educators everything, especially when we’re looking for root causes of students’ learning difficulties. Teachers must see that data stretch beyond what’s expressed on test company spreadsheets. The concept of data encompasses many kinds of information that help teachers know their students, and themselves as practitioners, in depth—and data can be interpreted in many nuanced ways.

James Popham (2001) is correct that teachers—and most administrators, I would add—are not assessment literate. And we should be. Remaining unaware of the range of assessments and how to use them and accepting (frequently inadequate) standardized tests as the single measure of success is irresponsible.

Getting Beyond Data as a Blind Date

For most teachers, getting acquainted with data happens as a kind of blind date. They come to a faculty meeting, and the principal introduces the data. Some schools use data coaches to facilitate the teacher-data relationship. Even if a coach helps teachers connect their student learning results with other kinds of data that reveal the how and why behind those results, data can still feel like a strange, unwelcome presence. The core problem is that none of this is initiated by teachers themselves.

When I consult with school administrators and district personnel who are excited—sometimes hyperexcited—about getting teachers interacting with classroom data, they inevitably ask, “How do I get my teachers interested in data—especially the unmotivated ones?” But teachers’ reluctance does not mean that they are unmotivated: Most teachers care about their students’ learning and want to excel at their work. The problem is that we frame data as an entity teachers need to meet and engage with, rather than as information that rises organically out of teachers’ work with learners. When teachers don’t embrace an idea or mandate, it’s often because they feel overburdened: They don’t see the time or need for a new professional love interest. There must always be a point to what administrators ask teachers to do with data.

Connecting Data to Questions

Questions and dialogue are key concepts here. I tell administrators that they should first urge teachers to think about what questions they would ideally like to ask to improve their classroom conditions, instruction, and repertoire of interventions. It helps to discuss with teachers the dangers of making assumptions about students and their learning.

Too often, questions about data in schools originate with administrators and district office personnel. Teachers feel no ownership or curiosity other than, Did we make our scores this year? and Do I get my bonus? Teachers cannot take the lead in data mining until they pose their own simple, measurable, and relevant queries.

Several years ago I helped the North Carolina Teacher Academy (2005) develop a learning module for teachers and administrators called Using Data to Build Classroom Learning Communities. This module was in demand. With NCLB pressures, principals and districts were looking for ways to help teachers focus on learning results, and teachers were looking for ways to make sense of all the standardized data being dumped on them. We field-tested the module with a group of teachers and administrators representing schools of all grade levels across North Carolina who were attending summer workshops at the North Carolina Teacher Academy. Through this process, I recognized the essential connection between teachers’ organic questions and data gathering.

We included in the module Alan Blankstein’s idea of the data notebook (2004), an ongoing collection of data a teacher gathers to help inform his or her instruction and interventions during the course of a year. Participants set up data notebooks and shared them with one another. We kept requirements for the notebooks open-ended but had teachers note three dimensions of any data they recorded: the frequency with which they collected these data; the type of teacher thinking this entry showed (descriptive, analytical, or reflective); and the kind of information it represented (such as evidence of student learning; demographics; teachers’, students’ and others’ perceptions; or instructional processes). For example, a teacher might record results of a survey he or she gave parents that gathered their impressions of the learning environment.

Prodding teachers to collect meaningful data on their own ensures that they will begin to ask questions, as I found out when I put together a sample data notebook. In the process of collecting, analyzing, and reflecting on information about my classes, I stepped outside my assumptions and understood students more clearly. I discovered a new way of thinking about my practice, but better still, the process caused me to ask such questions as, Are my students demonstrating growth in learning? or What do I need to change to accelerate growth? To satisfy these wonderings, I had to design assessments that would gather the information I needed and analyze the results, sometimes rethinking my methods as a consequence.

I now routinely identify questions and secure data that shed light on those questions as I teach. After 10 years of teaching 8th graders in an urban middle school, this past school year I began teaching high school seniors in a small rural setting. I wanted to know many things about my new students: how they perceived my style and methods, what and how much they were learning, and how their accomplishments matched the state curriculum and testing requirements. I sought a clear read on these questions through surveying my students, asking students to write reviews of their own learning and work products, mapping and analyzing trends in their grades, and even looking at their standardized test scores. If I hadn’t investigated these things, I’d have fallen into making distracting assumptions about the whys and hows of my students, their families, and the class’s learning.

Dialoguing With Data

This school year, I began to think beyond the model of each teacher examining data on an individual basis (such as in data notebooks) and to explore how teachers can share their questions and data among stakeholders at the classroom and school levels. As a teacher, I know that if students aren’t talking about it, then it’s not happening. And when it comes to data, if teachers aren’t talking about their data discoveries, no discoveries are happening.

As Judith Warren Little notes, in learning-rich conversations, there must be “a bridging back and forth between the particularities of what happened on [a given] day and more general principles and practices and ways of seeing” (Crow, 2008, p. 55). Group discussions about data can be the bridge connecting teachers’ day-to-day activities with deeper reflections. Data can play a central role in professional development that goes beyond attending an isolated workshop to creating a thriving professional learning community, as described by assessment guru Dylan Wiliam (2007/2008).

Compiling a data notebook is one thing, but talking about it with colleagues who share my students offers much broader potential for growth. Administrators who want teachers to embrace data and jump in as their own coaches must make room for this kind of dialogue.

To this end, almost all the data I collect, including some analysis and reflection, are available on my Web site (www.artofeducating.com). That gives students and families access to the data as well. Last school year, I e-mailed all of my students’ families links to the class’s average grades so that they could gauge their children’s performance in comparison with peers. I shared with students and parents the results of my end-of-year survey asking students for feedback about my class, including my reflections on what the survey revealed. This kind of data sharing and the resulting discussion was a tremendous help in developing relationships with students and parents at my new school, in part because parents could clearly see that I’m a thoughtful practitioner who cares about each student. Sharing data also elicited important information about my students’ learning needs.

Encouraging Expanded Views

I believe all teachers can learn to be both data lovers and their own personal data coaches if we encourage these expanded views about measuring teaching practice and learning. Teachers will need support both to become assessment literate and to adopt workable ways to gather, analyze, reflect on, and discuss data. Uncomfortable questions about the nature of standardized testing, school goals, and leadership may arise. Administrators should help their learning community respectfully talk through tough questions. They will build teacher capacity and leadership in the process.

Teaching is such a “particularistic endeavor” (Popham, 2008), that guiding teaching practice by one-size-fits-all test data will only take us so far. For the next phase of data’s role in education, I prefer Andy Hargreaves’s (2007) vision that “Teachers will need to be the drivers, not the driven” (p. 38).

References

Blankstein, A. M. (2004). Failure is not an option. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Crow, T. (2008). Declaration of interdependence (interview with Judith Warren Little). Journal of Staff Development, 29(3), 53–56.

Hargreaves, A. (2007). Five flaws of staff developments and the future beyond. Journal of Staff Development, 28(3), 37–38.

North Carolina Teacher Academy. (2005). Using data to build classroom learning communities. Morrisville, NC: Author.

Popham, W. J. (2001). The truth about testing: An educator’s call to action. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Popham, W. J. (2008). Transformative assessment. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Wiliam, D. (2007/2008). Changing classroom practice. Educational Leadership, 65(4), 36–42.

Santa Clause Is Coming to Town…

If you want to get a sneak preview of this year’s Thanksgiving Day Parade- just talk to one of our 4th graders

Fun Run fun with Limo and Lunch for our top fundraisers!

We had an awesome time together as the Arno top fundraisers got treated to lunch at Red Robins and a limo to get us there. The limo even had a fireplace to warm us up on that chilly day!

A special shout out to Red Robin for treating our kiddos to a free ice cream shake- Service was awesome with a very friendly staff, which really topped off the afternoon!

Rita Pierson- Every Kid Needs a Champion

Recess

Please keep in mind the following for recess.

1. With the exception of Kindergarten, there should not be other grade level recess during the morning hours. We have to preserve that for our prime blocks of learning as our kids will always be more receptive to learning in the a.m.

2. When you go out in the afternoon, please do not forget to call the office. Should another incident occur similar to last Friday where we could’t go out, we need to know if anyone is outside at the moment- a big safety issue. This also hinders the office from finding kids for early dismissal if they can’t find you.

SIP News

As you know our SIP meeting is taking place on Dec. 1, after Data Day. Please consider attending this important meeting on how our building needs to continue moving forward.

Sarah Kalis has offered to come in on Dec. 2 to train you on how to register students and read reports in Math Mania, part of our SIP. We will start that meeting @8:00-8:30 in the computer lab. I do have the questioning flip books in, if there is time, I will present those briefly, otherwise I will find another way to talk about them.

This is a game changer…

In case you have not read much about the 3rd grade reading proficiency bill yet, read below. This will be a game changer in terms of intensity of focus on the lower el, instruction, direction of certain funds, best practice, progress monitoring, and systems of support. It’s not signed yet, but it is expected to go through in some form.

House Bill 4822 Seeks to Improve Third Grade Reading Proficiency

November 4th, 2015

Category: General Education Law

MEAP test and NAEP assessment results demonstrate that in 2013-2014, large percentages of third and fourth graders in the state did not meet proficiency standards in reading. The “Third Grade Reading Workgroup Report” presented to Governor Snyder in June 2015 provided that when students are not proficient in reading by the fourth grade, it is more difficult for them to catch up because in fourth grade, students are not taught how to read as much as in previous grades. As a result, House Bill 4822 was introduced to the Michigan House of Representatives in August 2015 to amend the Michigan Revised School Code. It is currently before the House Committee on Education and has yet to be passed into law. In the meantime, it is important that school districts are aware of the potential programs and changes that could be required if the bill is passed into law.

The most notable provision of this bill would require that beginning in the 2017-2018 school year, a third grade student could only proceed to fourth grade if he or she met reading proficiency standards. If not, the student would have to repeat the third grade, but not more than once. A third grade student cannot proceed to the fourth grade unless: the student achieved a reading score less than one grade level behind on the state English language arts assessment; demonstrated a grade three reading level on a state standardized test; or demonstrated a grade three reading level through a student portfolio. A student enrolling for the first time in a school district in fourth grade must demonstrate reading proficiency. If a student remains in the third grade, a reading intervention program must be provided. A reading intervention program must include a qualified teacher, reading instruction, ongoing monitoring, and a “Read at Home” plan, among other requirements.

The bill does provide “good cause” exemptions for students to proceed to grade four without obtaining a grade three reading proficiency. The exemption may only be granted for one of the following four reasons: (1) the student has an IEP which states the student is ineligible to take the grade three state assessment; (2) the student has an IEP that demonstrates reading remediation yet continued deficiency; (3) the student is a limited English proficient student with less than three years of instruction in an English learner program; or (4) the student received intensive reading intervention for two or more years but is still deficient and previously retained in grade K, 1, 2, or 3. A good cause exemption may be requested by a parent or teacher. Then the school principal decides whether or not to recommend the student for the exemption and submits it in writing to the superintendent. The superintendent makes a final decision, also in writing. The parent of the child must be notified of the decision.

Pursuant to the bill, the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) would have to approve three or more screening, formative, and diagnostic reading assessment systems that districts may use. Factors such as the time required to conduct the assessment and the timeliness of reporting results would be considered in choosing the assessment systems. The MDE would also have to recommend or develop a reading/literacy coach model. The literacy coach would have to provide professional development to teachers. The literacy coach would have many responsibilities, including training teachers to diagnose and address reading deficiency, creating reading leadership teams at schools, and modeling instruction for teachers to kindergarten through third grade students. Literacy coaches cannot be assigned administrative functions within the district and cannot be assigned as a regular classroom teacher. The literacy coach must have various educational qualifications to be eligible.

Every school district would have to meet the following requirements beginning with the 2016-2017 academic year:

1) Select a reading assessment system from those approved by the MDE;

2) Develop an individualized Reading Improvement Plan for every student with a reading deficiency;

3) Provide notice to parents of a student’s deficiency in literacy or literacy delay and provide resources for the parents to use;

4) Provide professional development in reading literacy;

5) Employ a literacy coach;

6) Monitor and implement the literacy coach model.

Furthermore, Districts must provide reading intervention programs to students in grades K through three. The reading intervention programs may be student-specific, screen/monitor progress at least three times a year, and provide parents with a “Read at Home” plan. Reading intervention programs would include development in the five major reading components: (1) phonemic awareness, (2) phonics, (3) fluency, (4) vocabulary, and (5) comprehension. If a student is identified as being an English Language Learner, more specific intervention services would have to be implemented, such as instruction in academic vocabulary, instruction in the student’s native language and English, feedback in the student’s native language, etc.

With so many new requirements, many districts are worried about funding such new programs and resources. HB 4822 would result in increased costs to the state and local government. The state would have to fund the cost of educating those students held back. The district itself would have to fund costs associated with its new responsibilities under the bill. However, the bill makes clear that it does not require districts to supplant state funds with federal funds to implement the new programs. Nor does the bill prohibit districts from using federal funds to pay for the new programs required.

New Science News!

STATE BOARD ADOPTS IMPROVED

STATE SCIENCE STANDARDS

November12, 2015

LANSING – Michigan students will get a deeper understanding of science and its application in the world around them with new state science standards adopted this week by the State Board of Education.

The new standards for science education follow three years of development, review, and public information sessions on the proposed standards. The new Michigan K-12 Science Standards replace the standards adopted in 2006, and introduce science and engineering practices.

“These new Michigan Science Standards will help our terrific Michigan science educators engage young people in the doing of science, solving real world problems, and getting excited about pursuing science and engineering careers, said State Board President John Austin. “They also send a clear message that Michigan is serious about being the top science and engineering state, preparing the talent to solve the problems of the future right here in Michigan.”

Additionally, the new standards are a set of student performance expectations. These performance expectations incorporate three main elements:

• Disciplinary Core Ideas (science specific concepts in the life, earth, and physical sciences)

• Science and Engineering Practices (the practices of engaging in scientific investigation to answer questions, and engineering design to solve problems)

• Cross-Cutting Concepts (conceptual ideas common to all areas of science)

These expectations are also interwoven across disciplines, including connections to English language arts and math.

The standards come after a series of presentations to the State Board of Education starting in May 2014 that focused on various implementation considerations. This work culminated in a public comment period and series of informational sessions held throughout the state to address the standards and gather public comment.

The MDE received over 800 responses to a public survey on the updated standards, as well as hundreds of comments from the public information sessions held at 12 sites around the state.

The Michigan Department of Education (MDE) has provided all information related to the new standards athttp://michigan.gov/science. The MDE will begin a roll-out of the new standards through information sessions, guidance materials, and other supports through the remainder of the school year.

More passed by the state this year

Michigan Bake Sale Law in Effect for the 2015-16 School Year

October 20th, 2015

Category: General Education Law

In February 2015, a bill was introduced into the Michigan Senate providing exemptions for bake sales and other fundraisers that do not meet the nutritional standards of the USDA “All Foods Sold in Schools” Standards.

These “Smart Snacks in School” standards provided by the USDA were developed so that students were offered healthier foods in school and access to junk food was limited (see http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/allfoods_flyer.pdf). The Standards provide that any food sold in a school must be one of the following: (1) whole-grain rich; (2) have the first ingredient a fruit, vegetable, dairy product, or protein; (3) be a combination of food that contains at least ¼ cup of fruit and/or vegetable; or (4) contain 10% of the daily value of calcium, potassium, vitamin D, or dietary fiber. All snack items must be 200 calories or less and all entrée items 350 calories or less. Furthermore, schools should sell plain water, milk, or 100% fruit or vegetable juice.

The standards also specifically address fundraisers. If a fundraiser sells food items that meet the standards, such fundraisers are not limited. The standards also do not apply to fundraisers held during non-school hours and off-campus. However, the standards specifically provide an exemption for infrequent fundraisers that do not meet the nutritional standards and leave it up to each state to determine the frequency of such fundraisers.

Thus, Senate Bill 139 was introduced to the Senate to provide this exemption (seehttp://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2015-2016/publicact/pdf/2015-PA-0042.pdf). The bill allowed no more than three fundraisers per week that sold food items that do not meet the USDA standards. When the bill was sent to the Michigan House of Representatives for consideration, the number of allowed fundraisers was decreased to two per week. The Michigan Senate agreed and this version was passed into law on June 9, 2015, with immediate effect. Therefore, during the 2015/2016 school year and beyond, schools must limit the amount of bake sales with unhealthy foods to no more than two per week. However, the law further provides that if an ongoing fundraiser takes place at more than one time during the school day or throughout the school day, it is considered one single fundraiser.

The purpose of the USDA standards is to curb childhood obesity and promote healthy food choices among today’s youth. Although such bake sales provide student groups and the Boy and Girl Scouts good opportunities to fundraise for their organizations, the Michigan state legislature has voted to limit bake sales with unhealthy foods to two per week. However, if the fundraiser offers foods for sale that meet the nutritional standards, the two-per-week limit does not apply.

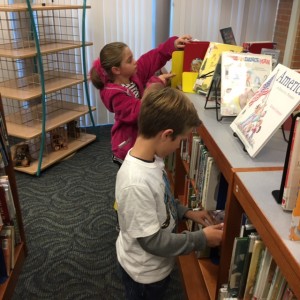

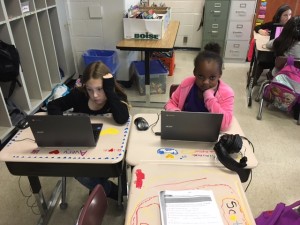

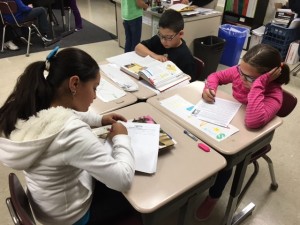

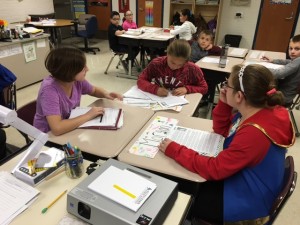

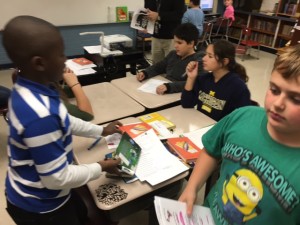

Arno Students Collaborating and Creating

Make it a GREAT week!